Abstract

Agriculture in the United States (US) cycles large quantities of nitrogen (N) to produce food, fuel, and fiber and is a major source of excess reactive nitrogen (Nr) in the environment. Nitrogen lost from cropping systems and animal operations moves to waterways, groundwater, and the atmosphere. Changes in climate and climate variability may further affect the ability of agricultural systems to conserve N. The N that escapes affects climate directly through the emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O), and indirectly through the loss of nitrate (NO3 −), nitrogen oxides (NO x ) and ammonia to downstream and downwind ecosystems that then emit some of the N received as N2O and NO x . Emissions of NO x lead to the formation of tropospheric ozone, a greenhouse gas that can also harm crops directly. There are many opportunities to mitigate the impact of agricultural N on climate and the impact of climate on agricultural N. Some are available today; many need further research; and all await effective incentives to become adopted. Research needs can be grouped into four major categories: (1) an improved understanding of agricultural N cycle responses to changing climate; (2) a systems-level understanding of important crop and animal systems sufficient to identify key interactions and feedbacks; (3) the further development and testing of quantitative models capable of predicting N-climate interactions with confidence across a wide variety of crop-soil-climate combinations; and (4) socioecological research to better understand the incentives necessary to achieve meaningful deployment of realistic solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrogen (N) is an essential element for plant and animal growth, and our ability to harness N in its reactive forms has fundamentally transformed how we produce food. The Haber–Bosch process, the industrial manufacture of ammonia (NH3), greatly accelerated the global production and dissemination of synthetic N fertilizers. This development marked the most significant human interference in the natural N cycle by removing a fundamental limit on crop yields, allowing for the adoption of high yielding cultivars and a corresponding increase in global harvests. Today, the approximately 100 Tg of reactive nitrogen (Nr) supplied from synthetic fertilizers is roughly equal to the total N fixed in natural terrestrial ecosystems (Houlton et al., this issue). Global per capita rates of N fertilizer consumption per year have risen from 0.2 kg in 1900 to 2 kg in 1950 to nearly 14 kg in 2000 (Smil 2001). Inevitably, this huge advance in global N use has been accompanied by considerable growth in Nr loss to the environment exacerbating atmospheric greenhouse gas (GHG) forcing. For example, atmospheric concentrations of nitrous oxide (N2O), the most long-lived form of gaseous Nr, have risen 18 % since 1750 (Houghton et al. 2001).

Fertilizers, manure, and legume dinitrogen (N2) fixation are the three main inputs of N to US agricultural soils. All three sources have been increasing over the past two decades, while the rate at which N is removed from cropping systems at harvest has been increasing at a slightly higher rate (Fig. 1), resulting in a slightly greater proportion of input recovery in 2007 than in 1987 (ERS 2012). The major forms of fertilizer used in the US are granular urea, fluid urea-ammonium nitrate (UAN), and anhydrous ammonia, with the use of urea-based fertilizers increasing and the use of anhydrous ammonia decreasing over time. Fertilizer N use in North America is forecast to grow 2–3 % per year from 2010 to 2016 (Heffer and Prud’homme 2011), and has been projected by one group to double to 28 Tg by 2030 (Tenkorang and Lowenberg-DeBoer 2009).

Inputs of N to US agricultural land, including recoverable manure, legume N2 fixation, and commercial fertilizers, as compared to removal by crops (adapted from IPNI 2012)

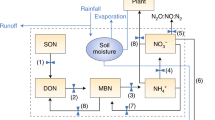

Nitrogen can take nine forms in terrestrial ecosystems based on different oxidative states (Robertson and Vitousek 2009). It is lost from agricultural systems in several of these forms; most of it less than a year after it enters the system (Galloway et al. 2003). Atmospheric emissions can occur as nitrogen dioxide (NO2), nitric oxide (NO), N2O, N2 or NH3 (Pinder et al., this issue; for the radiative forcing impacts of these compounds), while waterways receive inputs of nitrate (NO3 −) and dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) via leaching and runoff. Reactive N lost in one form can be converted to other forms of Nr and can “cascade” through several media and systems, contributing to a number of types of environmental pollution before returning to its original atmospheric form, N2 (Galloway et al. 2003; Houlton et al., this issue). Therefore any policy tackling N pollution must note the myriad of potential environmental sources and fates of N in the agricultural N cycle (Fig. 2) and attempt as holistic an approach as possible to avoid unintended outcomes.

Pathways of N cycling in agricultural ecosystems. Transformations of N shown in solid lines occur in all ecosystems; those shown with dashed lines are particular to (or particularly important within) agricultural systems. Major fluxes of N include, A, additions of industrial fertilizer; B, additions of organic N in manure and mulches; C, biological N2 fixation by microbes symbiotically associated with plants and by free-living microorganisms; D, atmospheric deposition of reactive N in oxidized forms (NO x ); E, atmospheric deposition of NH3 and NH4 +; F, mineralization of organic N via mobilzation of amino acids through the action of extracellular enzymes; G, mineralization of organic N via release of NH4 + by microbes; H, nitrification of NH4 + to NO3 −; I, plant uptake of available N; J, microbial immobilization—the uptake of biologically available N by microbes; K, losses of N in harvested products; L, losses of N in solution to streamwater and groundwater; M, denitrification to N2; N, NH3 volatilization from both fields and intensive animal production systems; O, losses of N2O produced during nitrification and denitrification; P, losses of NO x produced during nitrification and denitrification; Q, uptake of organic N by microbes during decomposition; R, dissimilatory reduction of NO3 − to NH4 +; S, consumption of plant N by animals; T, flux of N to soil from plant litter; and U, flux of N to soil from excretion or animal death (from Robertson and Vitousek 2009)

Major factors sustaining demand for N fertilizer use in the US include the outlook for continued large areas of corn cultivation, supported now by biofuel production goals and in the future by burgeoning food demand. At the same time, higher prices for fertilizer and pressures on producers for higher environmental performance are encouraging increased adoption of emerging fertilizer technologies such as precision agriculture and enhanced-efficiency fertilizers in controlled-release form or formulated with inhibitors of urease or nitrification.

Here we address the sources and fates of N in both cropping systems and animal agriculture and then assess some of the effects of climate change on the US agricultural N cycle as well as the effects of N use on climate forcing. We then summarize a number of mitigation opportunities and current policy efforts before concluding with future research needs.

Sources and fates of N in agriculture

Cropping systems

Agriculture in the US encompasses many different cropping systems designed to produce a diverse array of food, forage, fuel, and fiber products. All of these systems require adequate N, the nutrient that most commonly limits crop productivity, and all but a few leguminous crops depend on added N to achieve profitable yields.

Cropping system N sources

Legumes acquire their N from the atmosphere via rhizobial symbionts that reduce N2 to forms that can be used by plants for protein synthesis. Many legumes—soybeans and alfalfa among them—can meet 100 % of their N needs via N2 fixation, but more commonly a fraction of the N is provided by soil from the microbial conversion of soil organic matter (SOM) to NH4 + and NO3 −. Most of the N2 that is fixed ends up being assimilated into plant tissue, but some escapes from the roots to soil as root exudates. A portion of the plant-assimilated N is removed in crop harvest; the remainder becomes plant residue and decomposes to become SOM, ready for mineralization and subsequent crop uptake or loss from the ecosystem during the following seasons. When legumes are planted as fallow or winter cover crops following the main crop harvest, all of the N2 fixed becomes SOM as the cover crop is killed prior to planting the subsequent primary crop.

Synthetic fertilizer makes up the biggest source of N added to US cropping systems. Rates of fertilizer N additions typically range from <100 kg N ha−1 year−1 for small grains like wheat and perennial biofuel crops like switchgrass, to >200 kg N ha−1 year−1 for high-yielding corn and grass forage crops and some horticultural crops (Ribaudo et al. 2011). Theoretically, only as much N needs to be added as is removed in crop harvest, but crop N use is commonly inefficient. On average, only about 50 % of added N fertilizer is removed in annual grain crop harvest, for example (Robertson 1997).

Best practice calls for applying N at a time that is as close to the N need of the crop as possible to avoid excessive loss. In corn, for example, this usually means starter N at planting and the remainder following initial crop growth. In irrigated corn, fertilizer can be applied throughout the season in irrigation water. Often, however, equipment and labor availability together with uncertain weather drive decisions to add N fertilizer well before crop N needs. In 2005, for example, almost one-third of US corn cropland was fertilized the fall before spring planting (Ribaudo et al. 2011), leading to substantial potentials for N loss.

Nitrogen fertilizer additives and slow-release formulations are designed to delay added N from entering the soil’s soluble N pool until crop needs are greatest. Additives include nitrification inhibitors, which slow the transformation of NH4 + to NO3 − (Robertson and Groffman 2007). As a cation, NH4 + is less susceptible to leaching loss than is NO3 −. Although NO3 − is the form of N utilized by most crops, it also is the form that is most readily lost to the environment through leaching or denitrification to N2O, NO x [NO + NO2], and N2. Slow-release formulations usually coat the N fertilizer particle with a slowly dissolving shell of another compound or polymer that reacts to soil temperature and moisture. Additives and slow-release formulations are not widely used due to greater cost and inconsistent performance.

Manure represents the third major source of exogenous N to most US cropping systems. Approximately 6 Tg of manure N are produced annually in the US (USEPA 2011a). Because manure is often produced by livestock consuming grain imported from long distances and is expensive to transport, only a small percentage is returned to the field of origin; most manure is applied to nearby fields close to animal feeding operations. This regional N imbalance leads to less efficient nutrient cycling with greater losses to the environment (Fig. 3; Lanyon and Beegle 1989). Domestic animals are the largest source of US NH3 emissions, accounting for ~1.6 Tg N year−1 (USEPA 2011a). Certain forms of manure are more susceptible to volatilization than others because of their pH and NH3 content. Typical annual emissions of NH3 range from 40-1000 kg N/Mg from cattle and swine and 64-160 kg N/Mg from poultry, depending upon the type of housing and manure handling system used (Rotz 2004).

N flows through an integrated feed and animal production system. In the animal production portion of the system (upper part of figure), N is lost to the environment primarily in manure handling as NH3, N2O, and N2. Some N is exported in animal products and manure, but most is transferred in manure to the feed production system (lower part of diagram) where it is taken up by forage and feed crops, with some lost as NH3, N2O, N2, and NO3 −. Some of the N taken up is exported as surplus feed to other systems; most is used on-farm for animal production. Imported N includes that from fertilizer, biological N2 fixation, and deposition during feed production and during animal production as imported feed to make up feed production shortfalls. Line weights represent the relative amounts of flow among pathways

Soil organic matter is a fourth source of N in US cropping systems. While important on an annual basis—about 50 % of the N needs of fertilized crops are met by SOM mineralization—in most long-cropped soils SOM levels are stable because mineralized N is replaced by N in new crop residues as they decompose to SOM. Thus, SOM is not generally an important source of Nr in the environment except on recently converted lands (e.g., Gelfand et al. 2011) or on high SOM soils such as drained Histosols, which may quickly lose C and N on conversion to agriculture. There is some evidence, however, that long-cropped soils once thought to be equilibrated are newly losing SOM, perhaps because of climate change (e.g. Senthilkumar et al. 2009).

Cropping system N fates

The fate of N applied to cropland depends on many factors, some under management control and others related to soil, climate, and other environmental attributes. Once applied to soil, added N goes through a number of complex transformations, mostly biological, that lead to four major alternative fates (see Fig. 2): (1) plant uptake and subsequent removal in harvest; (2) loss to surface and groundwater via hydrologic flow as NO3 −, DON, and particulate N; (3) loss to the atmosphere as N2O, NO x , NH3, or N2; and (4) storage in the cropping system as inorganic N, in SOM derived from crop residues and microbial biomass, or, for perennial grass or tree crops, in long-lived plant parts such as roots and wood.

The hydrologic loss of NO3 − is typically the major vector of N lost to the environment from cropping systems that receive rainfall in excess of evapotranspiration. This loss of NO3 − can also be high from irrigated systems in drier climates when water applied exceeds crop transpiration need by only a few percent (Gehl et al. 2005). Hydrologic DON loss is minor in most cropping systems (van Kessel et al. 2009), as is particulate N loss in erosion, which usually represents the translocation of organic N from one part of the landscape to another rather than loss to the environment—although in areas of high erosion particulate N can be lost to surface waters via direct runoff.

Ammonium (NH4 +) loss from cropland tends to be important only when manure is applied to surface soils or when anhydrous ammonia or urea fertilizers are misapplied to dry soil, such that the NH3 that is added as anhydrous ammonia or formed from urea escapes to the atmosphere before it can be dissolved in the soil solution as NH4 +. Fertilizer misapplication in this way is inefficient and is more likely to occur during extended dry periods.

Nitrous oxide and NO are produced in soil by both nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria (Robertson and Groffman 2007). Nitrification is the oxidation of NH4 + to NO3 − with NO and N2O being metabolic by-products that escape to the atmosphere. Denitrification is the reduction of NO3 − to NO, N2O, and N2. The rates of N2O and NO production are highly variable in most soils, and are related both to the factors that affect rates of nitrification (mainly NH4 + availability) and denitrification (mainly NO3 −, C, and low O2 availability) as well as soil factors such as pH that affect the proportion of the end products that are emitted as NO and N2O (Robertson and Groffman 2007).

An important control on the rate of N gas production is the amount of N available to the bacteria that carry out the reactions. In almost all but very sandy soils, rates of nitrification and denitrification increase with increasing pools of inorganic N (e.g., NO3 −, NH4 +), and likewise, the rates of N2O and NO formation are best predicted by inorganic N availability. In unfertilized soil, N available to the bacteria that produce these gases is largely controlled by rates of N2 fixation, SOM turnover, and N deposition. In most cropped soils this N is largely controlled by rates of fertilization and SOM turnover. Because plants are good competitors for inorganic N, plant uptake can reduce the amount of N that would otherwise be available for N gas production or hydrologic loss.

Nitrogen use efficiency (NUE)—and in particular N-fertilizer use efficiency—is therefore a good general metric of N conservation in cropping systems. Maximizing the fertilizer N that makes it into the crop will, in general, minimize the N that is free for loss to the environment. The objective of crop N management is to improve the efficiency of plant use of N fertilizers. Strategies to improve system-wide fertilizer use efficiency are therefore of utmost importance for both reducing the impact of climate on crop N use and for reducing the impact of agriculture on climate, as discussed later.

Animal systems

Animal agriculture in the US today encompasses a number of different domesticated animals raised for meat, fiber, milk, and eggs in a variety of housing arrangements ranging from high-density confined-animal feeding operations (CAFOs) to extensive rangeland. All systems have in common the provision of high quality feed and forage that contains protein-N in excess of the animals’ N need. Excess N is excreted and subsequently available for loss to the environment, where it has a number of potential fates.

Animal system N sources

Animal agriculture in the US produces about 131 Tg of meat, eggs, dairy and other animal products using production systems that vary widely by animal species, type of product, and the economic, geographic and cultural characteristics of the production region (ERS 2011). The manure produced by farm animals is considered the major source of gaseous NH3 emission in the US (USEPA 2011a). Manure is a significant contributor to N2O and NO x fluxes both during handling and following soil application (CAST 2004), where it is subject to the same potential fates as synthetic N additions. Manure applied to fields without growing crops is susceptible to substantial N loss when the manure N is transformed from organic to inorganic (e.g., NH4 + and NO3 −) forms. At a very general level, animal production systems involve the production of feed, preparation and delivery of feed rations to the animals, and the removal and recycling of manure nutrients. The overall production strategy greatly affects the efficiency of N use and its influence on the environment.

The major animal species used for animal agriculture in the US include dairy and beef cattle, swine, and poultry. Cattle are ruminant animals that require a different feeding strategy than non-ruminants such as swine and poultry (Hristov et al. 2011). Most swine, poultry and beef feedlot systems are managed as independent feeding operations (top half of Fig. 3), where most or all feed is imported, often from long distances.

The production of all confined animal species requires large amounts of N for feed. For all species, protein requirements must be met for maximum production. Protein is comprised of amino acids required by all organisms for maintenance, growth, and reproduction (NRC 1994, 1998, 2000, 2001). Animals require 20 essential amino acids in amounts that vary with animal age and productivity. Proteins on average contain 16 % N; therefore matching amino acid levels in rations to those required by the animal is complex and bears strongly on efficient N use. Unused protein and non-protein N in animal diets is excreted in manure where it can be lost to the environment as Nr.

During harvest and storage, a small portion of the protein in feed is lost and the remainder can be transformed to different forms (Rotz and Muck 1994). For example, a large portion of the forage fed to cattle is preserved through ensiling, which breaks down plant proteins to forms that are used less efficiently by the animals (Rooke and Hatfield 2003).

Much progress has been made in recent years in determining the nutrient requirements of animals and matching those requirements to that available in feed rations in order to maximize production (NRC 1994, 1998, 2000, 2001). For ruminant animals, suitable fiber levels must be maintained for proper rumen function, which enforces the use of forage in diets and limits the amount of grain and other concentrate feeds that can be used. Some amino acids are required to meet the requirements of microorganisms in the rumen while others are needed in the intestinal tract and must make it through the rumen intact (NRC 2000, 2001). Preparing rations that supplement available forage with the proper amino acids to meet animal requirements is difficult due to varying amounts and types of forage available though the year along with their varying nutrient concentrations. Grazing animals provide an additional challenge since the producer has less control over their diets. Pasture forage tends to have more protein and more rapidly degrading protein than is required, which leads to less efficient N use and greater N excretion (Van Soest 1994). A study on grazing dairy farms in the northeastern US has shown total protein was being overfed by 20–80 % (Soder and Muller 2007).

Non-ruminant animal feeding does not have the complication of fiber requirements. Grains and other concentrate feeds have a more consistent concentration of protein and other nutrients, so protein requirements can be met more precisely. Synthetic amino acids are also commonly used to meet nutritional requirements with greater accuracy throughout animal growth cycles (Keshavarz and Austic 2004).

Animal system N fates

In general, 65–90 % of the N consumed in feed is excreted in manure with the remainder retained in body tissue and the milk, eggs, or other products produced (Hristov et al. 2011; Rotz 2004). With good feeding practices for cattle and swine, about 50 % of the N excreted in feces is in a relatively stable organic form. The remainder, including most of the excess N consumed, is excreted in urine as urea. For poultry, a large portion of the excreted N is uric acid, which decomposes to form urea. When deposited on the floor of the housing facility, the urea comes in contact with urease enzymes, which rapidly transform the urea N to NH4 +. At a rate dependent upon temperature, pH and other manure characteristics, the NH4 + forms NH3, which is readily volatilized (Hristov et al. 2011; Montes et al. 2009).

On a barn floor, for example, where manure is removed at least once per day, NH3 emissions vary with temperature and are relatively low in cold winter weather (Montes et al. 2009). In warm weather or on a surface such as an open lot where manure is not removed, nearly all of the urea-N can be lost to the atmosphere as NH3 (Hristov et al. 2011; Rotz 2004). Some housing systems use a bedded pack, whereby manure and bedding materials accumulate on the barn floor. With this strategy, a portion of the NH4 + is absorbed into the bedding material, emitting more NH3 than if it were it deposited on a scraped floor, but less than if it were deposited in an open lot. Bedded pack and open lot surfaces both provide aerobic and anaerobic conditions to support both nitrification and denitrification, creating emissions of N2O and N2 (Rotz 2004).

Manure removed from barns can be handled in solid, semi-solid, slurry or liquid forms. Solid manure is relatively dry, often scraped from open lot surfaces where most of the labile N has been emitted as NH3 (Hristov et al. 2011). Semi-solid manure is formed using bedding material to absorb manure moisture. This type of manure is typically not stored for long periods and may be spread on crop and pastures each day of the year as it is produced. Slurry is formed by scraping manure from the floor of free stall and similar barns designed to use less bedding material. Liquid manure is typically formed by using a solids separator to remove a major portion of the manure particles, leaving the manure solution with less than 5 % dry matter content. Manure solids can be composted and used as bedding material, with most of the NH4 + remaining in the liquid portion (Meyer et al. 2007). Both slurry and liquid manure are typically stored for 4-6 months and in some cases up to a full year to allow the nutrients to be applied to fields at a time when they are best used by growing crops or grassland. However, this requires a storage capacity that many operations lack and consequently it is not unusual for manure to be spread on frozen fields or pastures during the winter.

During long term manure storage, the organic N portion in the manure slowly decomposes, producing NH4 +. If semi-solid manure is stored, it is placed in a stack where NH3 emissions occur and nitrification and denitrification processes generate N2O, NO x and N2 emissions. About 10–20 % of the N entering storage is lost mainly as NH3 (Rotz 2004). Slurry manure is typically stored in a tank. When manure is continually added to the surface of the tank, up to 30 % of the N can be lost as NH3, but little or no N2O escapes, because anaerobic conditions inhibit nitrification, thus preventing conversion to NO3 − and subsequent denitrification. When manure is pumped into the bottom of the tank, a crust of manure solids can form on the surface, reducing emissions of NH3 by up to 80 %. However, nitrification and denitrification can occur within this crust, thus emitting N2O (Petersen and Miller 2006). Liquid manure is commonly stored in a lined earthen basin or lagoon where NH3, N2O and N2 losses are relatively high (Harper et al. 2004). When a multiple stage lagoon (e.g., flow from a facultative to anaerobic lagoon) is used, up to 90 % of the N can be lost or removed between the inlet and outlet.

Most manure is applied to crop or grassland as fertilizer. Methods of manure application include broadcast application to the field surface, subsurface injection, and irrigation. When manure is broadcast spread, any remaining NH4 + in the manure is rapidly volatilized to NH3 (Gènermont and Cellier 1997), although at least half can be retained if the manure is tilled into the soil within several hours of application (Rotz et al. 2011). Subsurface injection can also greatly reduce or even eliminate NH3 emission depending upon injection depth (Rotz et al. 2011; Ndegwa et al. 2008). Irrigation is often used to apply liquid manure, and a portion of manure-N content is lost as NH3 during irrigation. However, if the manure infiltrates rapidly into the soil, N will be retained as NH4 + (Sommer et al. 2003). Application losses vary from 2 % of the manure N applied through deep soil injection to 30 % of the N applied through surface spreading without soil incorporation (Rotz 2004).

Climate–nitrogen interactions

Climate and agricultural N interact in complex ways. Some of the interactions are direct, such as changes in climate patterns that prompt farmers to adapt their cropping systems to higher temperatures and changes in rainfall patterns. Some of the interactions are indirect, such as changing consumption patterns of oil and natural gas (used as feedstocks for NH3 production) as a result of climate policies, which may subsequently affect fertilizer prices and, thus, fertilizer consumption and consequently Nr escape. However, agriculture is not only affected by climate change, but also contributes to climate change by contributing GHGs to the atmosphere. We consider both climate effects on N cycling and farm N cycle effects on climate change in the sections below.

Climate effects on agricultural N cycling

Climate change affects agricultural N cycling mainly through its impact on changing patterns of temperature and rainfall. Effects also occur due to changes in the chemical climate—in particular via changes in atmospheric concentrations of ozone (O3) and carbon dioxide (CO2).

Ozone, climate, and agricultural yield impacts

Nitrogen oxides (NO x = NO + NO2) are key precursors of tropospheric O3. Ozone harms crops and thereby affects crop N use and Nr escape. Ozone is produced in the troposphere by the catalytic reactions of NO x with carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4), and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs) in the presence of sunlight (photolysis). Production of O3 is a highly non-linear function of the emission of these precursors (NRC 1991), some of which (NO x and CH4 in particular) are produced by agriculture (Yienger and Levy 1995; Karl et al. 2009; Hudman et al. 2010). Due to these non-linearities, the O3 production efficiency per unit NO x emitted is high in rural areas. Furthermore, increases in temperature can also lead to higher rates of precursor emission and O3 formation.

Field experiments in the US, Europe, and Asia have shown that surface O3 causes substantial damage to many plants and agricultural crops, including increased susceptibility to disease, reduced growth and reproductive capacity, increased senescence, and reductions in crop yields (Mauzerall and Wang 2001). Based on the large-scale experimental studies of the National Crop Loss Assessment Network (NCLAN) conducted in the US in the 1980s (Heagle 1989; Heck 1989), the US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) estimated that the yields of about one third of US crops were reduced by 10 % due to ambient O3 concentrations during this time (USEPA 1996). Model simulations of O3 used with the established NCLAN concentration and yield response relationships predict larger effects for grain crops for 2000 and 2030 (Avnery et al. 2011a, b).

Agricultural soils are a minor but significant source of atmospheric NO x (Robertson and Vitousek 2009), with NO x emissions (“P” in Fig. 2) typically enhanced following fertilizer application, precipitation, and elevated temperature (Butterbach-Bahl et al. 2009). In a recent top-down analysis, emissions from agricultural soils summed to about 14 % of global surface emissions (Jaeglé et al. 2005). Hence, increasing fertilizer use in response to a growing global population requiring food and biofuel in a warming climate may lead to higher soil NO x emissions and consequently increased O3 production with resulting adverse impacts on crop yields. Emissions of NO x from industrial and vehicle sources are expected to decrease in the US over the next several decades, increasing the relative contribution from agriculture to total US NO x emissions (Peel et al., this issue). Thus NO x emissions from agricultural regions will likely have a proportionally larger impact on rural O3 concentrations, and hence on crop yields, in the future.

Large-scale, comprehensive field studies in the US and Europe in the 1980s/1990s showed a wide range of crop sensitivities to O3, both among different crops and within cultivars of the same crop (Heagle 1989; Heck 1989; Krupa et al. 1998). Crop varieties used today appear to exhibit sensitivity to O3 that is on average at least as great as that seen in earlier field studies (Long et al. 2005; Emberson et al. 2009). Ozone sensitivity may thus be an overlooked factor in cultivar choice, especially if variety development and breeding trials are conducted in areas of low or moderate O3 impact.

The observed correlation between surface O3 and temperature in polluted regions points to a detrimental effect of warming. Although there is regional variability, observations in the US have shown higher surface O3 concentrations as temperatures increase (see Fig. 4). In addition, coupled chemistry—climate model simulations indicate that with no change in the emission of O3 precursors, climate warming itself will likely result in increased surface O3 concentrations in many parts of the US (Jacob and Winner 2009). This is frequently termed the “climate penalty” and it applies to penalties both for agricultural productivity and human health (Peel et al., this issue). Projected increases in O3 vary among models, but are typically in the 1–10 ppb range over the next several decades, implying that stronger emission controls will be needed in order to meet a given O3 air quality standard. Although higher water vapor in the future climate is expected to decrease O3 over remote oceanic regions, the opposite may occur for polluted continental regions (Jacob and Winner 2009).

Observed probability that maximum daily average ozone will exceed 80 ppb for a given daily maximum temperature (1980–1998 data) for different parts of the US (adapted from Jacob and Winner 2009)

Temperature effects

Temperature will affect both crop and animal production systems. Warming temperatures will affect crop productivity, mainly because most physiological processes related to crop growth and yield are highly sensitive to temperature, and crops have a specific temperature range for maximum yields (Hatfield et al. 2008, 2011). The response of crops to temperature may be complex, non-linear, and exhibit threshold effects. Maximum crop yields for corn, soybeans, and cotton are found at temperatures of 29, 30, and 32 °C, respectively. The slopes of the decline in yield above optimum temperatures are significantly steeper than the incline in yield below optimal temperature (Schlenker and Roberts 2009).

There is debate over the effect of temperature on agricultural yields. Recent research indicates that from 1980 to 2008 global yields of maize and wheat declined by 3.8 and 5.5 %, respectively, relative to a counterfactual without climate trends (Lobell et al. 2011). However, these global declines were driven by responses in low latitude countries, where temperatures in tropical locations may exceed optimal ranges, resulting in a significant reduction in yields. In contrast, higher temperatures may benefit crop productivity in some mid- to high latitude regions by increasing the length of the growing season as well as the amount of land suitable for cultivation. Fischer et al. (2005) project an increase in potential agricultural land of 40, 16, 64, and 10 % in North America, Europe, Russia, and East Asia, respectively, driving potential global cereal production improvements of 1.9–3.0 Gt by 2080 depending on the climate change scenario considered. However, temperature also affects the rate of plant development, and even brief exposure to higher temperatures may shorten growing periods and threaten yields if exposure occurs during important development stages such as flowering and grain filling (Wheeler et al. 2000; Wollenweber et al. 2003).

Higher temperatures may also accelerate SOM turnover, leading to lower soil C stores (Davidson and Janssens 2006; Knorr et al. 2005, Conant et al. 2008) even in arable soils. In some cases (e.g., Senthilkumar et al. 2009), accelerated C loss has been attributed to higher wintertime temperatures, which in cropped systems would release additional N to the soil at a time when plants are not available to immobilize it.

The balance between warmer temperatures and increasing/decreasing rainfall will be important for determining whether there is an increase or decrease in emissions of Nr gases (N2O, NO x ; “O” and “P” in Fig. 2) per unit of fertilizer applied to cropping systems. More research is needed to illuminate these changes on both a regional and global basis.

Projected temperature changes will also directly and indirectly affect animal production. The primary direct impact will be related to heat stress due to increasing ambient temperatures. Heat stress causes reduced feed intake, increased water intake, higher body temperatures, increased respiration, decreased activity, and hormonal and metabolic changes, which in turn lead to reduced production, reduced reproduction, and increased mortality (Nardone et al. 2010). Under our current climate, heat stress is estimated to cause an annual economic loss of 1.7–2.4 billion dollars in the US (St-Pierre et al. 2003). Future shortages of water may also directly impact animal production and exacerbate the heat stress issue.

Indirect effects include changes in feeding practices due to the adaptation of crop type, yield, and nutritive content to changes in climate. Furthermore, adaptation to new feeds may also affect feed value and N use efficiency. Rates of NH3 emissions are also very sensitive to temperature (Montes et al. 2009), such that increasing ambient temperatures will also increase this source of N loss throughout all phases of manure handling. Overall, the net effect of these changes in the N cycle in response to heat stress is likely a reduction in N use efficiency of animal systems.

Precipitation impacts on crop response to and recovery of N

The quantity, frequency, and intensity of precipitation and evapotranspiration throughout much of the world will likely be altered due to rising global surface temperatures (Meehl et al. 2007). Precipitation increased by 7–12 % in the middle to high latitudes of the northern hemisphere during the twentieth century, particularly during autumn and winter when rains and snowfall were more intense. However, these increases varied both spatially and temporally (IPCC 2001). Areas that experience increases in mean precipitation, particularly tropical and high latitude regions, are also projected to have an increased intensity of precipitation events. Geographic regions where precipitation decreases (e.g., most subtropical and mid-latitude regions) are expected to have increased sporadic precipitation events of increased strength, with longer dry periods between events. Projected increases in summer dryness from increasing surface temperatures also indicate a greater risk of probable drought. Notable changes in precipitation extremes have already been observed, and projected changes would extend trends already underway (USGCRP 2009; Meehl et al. 2007).

Intensification of precipitation in spring and excessively wet winters can delay crop planting, increase plant diseases, retard plant growth, and cause flooding, runoff, and erosion—all of which can harm crop production and reduce crop yields and economic returns. Additionally, extreme wet cycles can result in substantial losses of Nr to the environment, through transport and leaching of NO3 − (“L” in Fig. 2) especially in regions where artificial subsurface drainage (e.g., tiles) removes excess soil water from fields, and through gaseous losses of N2O (“O” in Fig. 2). Nitrate leaching is a problem that is exacerbated when large amounts of soil NO3 − are present after fertilizer application and before the period of peak crop N demand (“I” in Fig. 2) (Davidson et al. 2012).

Increases in drought frequency and intensity also adversely affect crop growth and yield, ultimately impacting nutrient use and uptake efficiency. Drought also increases the demand for irrigation which affects regional water resources as well as Nr movement in the soil system. Fertilizer N is typically applied prior to or shortly after crop planting (“A” in Fig. 2), and is usually applied on the basis of expected yields at rates to produce historically maximum crop yields for a given location. Thus, environmental factors that limit crop growth and yield during the growing season, including both drought and excessive moisture, would result in especially high Nr loss due to reduced crop uptake, particularly when significant precipitation events or prolonged wet periods occur after the growing season.

Occurrences of drought or excessive moisture affect not only crop growth and subsequent nutrient use, but also soil N turnover within agricultural systems (“F”, “G”, “H”, “J”, “R”, “Q” in Fig. 2). Short- and long-term fluctuations in precipitation are closely tied to the spatial and temporal N dynamics of the system. During periods of drought or seasonal water deficit, an overall decrease in N turnover typically follows as a result of shifts in soil and atmospheric N dynamics.

Ecosystem N loss mechanisms are highly sensitive to fluctuations and variability in both precipitation timing and amount (Larsen et al. 2011). Seasonal and periodic droughts affect net primary productivity, plant N uptake, soil microbial activity, N2O flux, NO3 − leaching, and denitrification (Emmett et al. 2004; Davidson et al. 2008; Sardans et al. 2008; Larsen et al. 2011). Further, drought reduces net soil respiration and when soil is wetted following a drought, large fluxes of NO and N2O rapidly occur (Davidson 1992; Bergsma et al. 2002; Borken et al. 2006). The pronounced affects of extreme precipitation fluxes and drought on soil Nr dynamics thus affect soil N availability to planted crops and the response of crops to fertilizer N sources.

Effect of increased ambient CO2 on crop N demand

Atmospheric CO2 concentrations have increased from 270 to 384 ppm since the Industrial Revolution. Numerous studies have evaluated crop response to rising CO2 concentration, sometimes referred to as the CO2 fertilization effect. Many crop plants, including wheat and soybean, demonstrate increased growth and seed yield in response to increased CO2. Elevated CO2 may also improve crop water use efficiency and drought tolerance by reducing conductance of CO2 and water vapor through leaf stomata.

Larsen et al. (2011) report increased C to N ratio (C/N) in aboveground plant biomass of a semi-natural ecosystem with elevated CO2. However, they conclude that drought dominated the plant response to elevated CO2, and that the reduced N turnover stemming from drought and warming may act to reduce the potential plant growth response to rising atmospheric CO2.

Crop response depends in part on the major photosynthetic pathway employed by a given crop. Plants with a C3 metabolism have different CO2 and temperature response curves than those with a C4 pathway. Most crops grown in the US are C3 plants, but several C4 crops are economically important including corn, sorghum, sugar cane, and warm season grasses proposed for biofuel feedstocks, such as switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) and giant miscanthus (Miscanthus × giganteus).

Leakey et al. (2009) recently summarized the results of 15 major Free-Air CO2 Enrichment (FACE) experiments that measured the impact of elevated CO2 on plants over multiple seasons and/or crop life cycles. They reported several important effects, including:

-

Photosynthetic C uptake of C3 plants is enhanced by elevated CO2 despite acclimation of photosynthetic capacity, with an expected C gain of 19–46 % for plants grown at CO2 levels projected for the mid-century;

-

For C3 plants, photosynthetic N use efficiency (PNUE), determined as the net amount of CO2 assimilated per unit of leaf N, increases with increasing CO2. The observed increase is primarily driven by enhanced CO2 uptake and not by redistribution of foliar N.

-

Plant water use consistently declines with increasing CO2, resulting in greater soil moisture availability. The decline in water use is driven by reduced stomatal conductance coupled with decreased canopy evapotranspiration with elevated CO2.

-

Carbon uptake in C4 plants is not directly stimulated by elevated CO2 except in drought situations. However, there is a potential for increased C4 plant growth at elevated CO2. Decreased water use and reduced drought stress at elevated CO2 improves C4 plant water relations and indirectly enhances photosynthesis, growth, and yield.

-

The increase in C3 photosynthesis stemming from elevated CO2 in FACE experiments was greater than the increases in biomass or crop yield, suggesting that photosynthetic response cannot itself predict crop performance. Prior predictions of crop growth based on theory and observations in laboratories or growth chambers systematically overestimated yields of major food crops compared with FACE experimental results.

Cumulatively, the effects of elevated CO2 impact the growth response and potential yield of crops. The impact of these changes on crop N uptake and demand and crop response to fertilizer N warrants further investigation.

Elevated CO2 may also directly affect soil N transformations and gaseous Nr loss due to increased soil C availability and changes in soil–plant water relations (Luo and Mooney 1999). Soil processes that involve Nr may be altered indirectly through changes in plant biomass, root exudates, and microbial community structure (Cantarel et al. 2011).

Greenhouse gas forcing due to use of N in agriculture

Agricultural N contributes to GHG forcing in several ways. Farming results in the direct release of several GHGs and GHG precursors, including CO2, N2O, NO x , and CH4. Some of these gases are also released indirectly by farming—in downwind and downstream ecosystems that receive Nr initially in the form of NH3 volatilized and NO3 − leached from farm systems. Tillage also has a well-known and direct effect on CO2 release from farmed soils (Davidson and Ackerman 1993; Grandy and Robertson 2006), and there may be an interaction with N use. Additionally, the manufacture of N fertilizer emits CO2 directly to the atmosphere.

Nitrous oxide emissions

Nitrous oxide is not reactive in the troposphere but is a powerful GHG—approximately 300 times more potent than CO2 on a molar basis, and atmospheric concentrations have increased consistently from 270 ppb during pre-industrial times to today’s concentrations of approximately 320 ppb. This increase in N2O has contributed about 6 % of the total GHG forcing that drives climate change (Forster et al. 2007). While this is not a large percentage, the anthropogenic N2O flux is equivalent to 1.0 Pg C year−1 when converted to C equivalents using 100-year global warming potentials (Robertson 2004; Prinn 2004), which is of the same magnitude as the contemporary net atmospheric CO2 increase of 4.1 Pg C year−1 (Canadell et al. 2007).

About 80 % of the N2O added to the atmosphere annually by human activities is associated with agriculture. About 60 % of this is emitted from agricultural soils, 30 % from animal waste treatment, and 10 % from burning crop residues and vegetation cleared for new agricultural activities (Robertson 2004; Houghton et al. 2001). Row crop agriculture is thus responsible for about 50 % of the global anthropogenic N2O flux (Robertson 2004). Due in part to its high global warming potential, N2O is a major target for offset projects that can be included in cap and trade markets due to the high payback associated with the mitigation of N2O emissions (Millar et al. 2010).

Fluxes of N2O are highest where inorganic N is readily available (Bouwman et al. 1993). Thus soils fertilized with N are major sources of N2O, although fluxes can also be high in soils with high SOM stores that are rapidly mineralizing N, such as drained organic soils (e.g., Histosols in the USDA soil taxonomy nomenclature). Hundreds of field experiments have shown the amount of N fertilizer applied to be the strongest manageable predictor of N2O fluxes in all major cropping systems. In addition to the amount of N applied, N2O fluxes can also be influenced by the formulation, timing, and placement of N fertilizers, and by agronomic practices that affect N availability in soils, such as tillage and residue management.

On average, about 0.5–3 % of N applied to cropped soils is emitted as N2O to the atmosphere (Stehfest and Bouwman 2006; Linquist et al. 2012). The range is due mainly to variation among sites and is well-recognized and expected based on soils, climate, and fertilizer practices. Furthermore, emission rates may be even higher where N input levels exceed the demand of the crop (e.g., McSwiney and Robertson 2005; Jarecki et al. 2009; Hoben et al. 2011). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Tier 1 methodologies for national GHG inventories (De Klein et al. 2006) assume an emission factor (EF) for N2O emissions from cropped soils to be 1 % of the N inputs from fertilizer, crop residues, and SOM mineralization where SOM is changing, with an additional premium from drained organic soils (Histosols). Recent evidence suggests that these rates may be even higher at N input levels that exceed the crop demand for N (McSwiney and Robertson 2005; Ma et al. 2009; van Groenigen et al. 2010; Hoben et al. 2011).

So-called indirect emissions of N2O are emitted from downwind and downstream ecosystems when Nr escapes to areas where conditions for N2O production are favorable. Indirect emissions are even more difficult to estimate than direct emissions because there is uncertainty in both the amount of Nr that escapes and the portion of N that is then converted to N2O. IPCC Tier 1 methodologies assume that 0.75 % of the N that is leached from cropped systems and 1 % of the N that is volatilized and subsequently deposited to downwind ecosystems are emitted later as N2O (De Klein et al. 2006). Recent results suggest that the EF for leached N depends on the type of waterway (Beaulieu et al. 2011), and it is also likely that the EF’s for volatilized and re-deposited N will vary depending on the N status (e.g., limiting or non-limiting) of the receiving ecosystem.

Nitrogen oxides emissions

Emissions of NO x have increased substantially due to human activities, including agriculture (Houlton et al., this issue). In the mid-1990s, agricultural sources, broadly defined to include residue burning and land clearing, in addition to direct fluxes from soils, were equivalent to all natural sources and comprised about 25 % of all anthropogenic NO x emissions (Robertson and Vitousek 2009).

In soil the NO that is produced is rapidly oxidized to NO2 in the atmosphere. Soil NO can be produced by chemodenitrification when HNO2 spontaneously decomposes to NO, but more commonly NO is produced as a metabolic intermediate during nitrification and denitrification (Robertson and Groffman 2007). Cropland NO x emissions tend to be highly episodic, and in some cropped systems (e.g., Matson et al. 1998) the magnitude of NO x emissions can rival those of N2O. In general, however, Stehfest and Bouwman (2006) estimate that global NO-N emissions from cropland and grassland are less than half of the global N2O-N emissions. Most NO is formed from the same biological sources as N2O (i.e., nitrification and denitrification); therefore, NO emissions are also affected by the same environmental and agronomic factors, including fertilizer application rate and soil moisture.

Although NO x is not a GHG it plays a substantial role in tropospheric photochemistry (Pinder et al., this issue) affecting atmospheric concentrations of the GHGs O3 and CH4. Eventually NO x is deposited on downwind ecosystems in gaseous, particulate, or dissolved forms, where it undergoes the same fate as other Nr inputs, including potential transformation to N2O.

Methane fluxes

Lowland rice cultivation represents the only major source of CH4 from established cropping systems; about 40 Tg year−1 are emitted from rice soils worldwide (Sass et al. 1999). About 142 Tg year−1 of CH4 associated with agriculture are also produced by ruminant livestock, animal waste treatment, and when agricultural residues and land cleared for agriculture are burned (Robertson 2004). However, these sources are not much affected by the use of N in agriculture. In contrast, the application of organic N amendments such as farmyard manure, specialty mixes of organic fertilizer, and incorporated cover crops to rice fields generally increase CH4 emissions (Qin et al. 2010). The influence of synthetic fertilizers on CH4 emissions from rice fields is less consistent and not well understood (Zuo et al. 2005).

Methane consumption in soil (CH4 oxidation or methanotrophy), in contrast to CH4 production (methanogenesis), is broadly affected by agricultural N use. Methanotrophic bacteria capable of consuming atmospheric CH4 are found in most aerobic soils, including arable lands, making the uptake of CH4 globally important: The size of the global soil sink of CH4 (about 30 Tg CH4 year−1) is the same magnitude as the annual atmospheric increase of CH4 (about 37 Tg CH4 year−1). In unmanaged ecosystems on well-drained soils, CH4 uptake is co-limited by both the rate at which it diffuses to soil microsites and methanotrph activity (von Fischer et al. 2009). Diffusion is regulated by physical factors—principally moisture but also temperature and soil structure—as well as the concentration of CH4 in the bulk soil atmosphere.

Agricultural management typically diminishes soil CH4 oxidation approximately 70 % or more (Mosier et al. 1991; Robertson et al. 2000; Smith et al. 2000) for at least as long as the soil is farmed. The mechanism for this suppression is not well understood; likely it is related to soil N availability as affected by enhanced N mineralization, fertilizer, and other N inputs (Steudler et al. 1989; Suwanwaree and Robertson 2005). Ammonium is known to competitively inhibit CH4 monooxygenase, the principal enzyme responsible for oxidation at atmospheric concentrations. Recent evidence suggests that microbial diversity may also play an important role (Levine et al. 2011).

While additional agricultural N use will not much affect CH4 oxidation in already-cropped soils, Nr that escapes from agricultural to downwind and downstream ecosystems may inhibit CH4 oxidation in those systems, attenuating a significant CH4 sink that would otherwise continue to absorb atmospheric CH4. The degree to which current natural ecosystems are affected is unknown, mainly because most CH4 oxidation experiments to date have been conducted with relatively high levels of N addition.

Tillage and soil C storage

Nationally, US croplands are in approximate C balance (CAST 2011). An estimated increase of 13 Tg C on cropped mineral soils is largely balanced by emissions from cultivated organic soils (Histosols) and from land recently converted to cropland (Ogle et al. 2010; USEPA 2011b). Increases appear to be due to a long-term trend of increasing crop residue production, reductions in tillage intensity (Horowitz et al. 2010), and conversion of annual cropland to perennial grasslands for hay, pasture, and conservation set-asides (CAST 2011).

The influence of N fertilizer use on cropland soil C storage is unclear and currently under active debate. On the one hand, the argument is that N fertilizer increases soil C because increased above- and belowground residue production parallels increased yields. In addition, because residue C:N ratios have not changed, the additional crop residues should contribute to additional soil C stores (Glendining and Powlson 1995; Powlson et al. 2010). On the other hand, there are studies that document variable effects of inorganic N on SOM oxidation (Pinder et al., this issue; Neff et al. 2002), with recent studies noting declines in soil C storage in well-equilibrated, fertilized, long-term plots despite large and steady increases in crop residue inputs (Khan et al. 2007). An additional consideration is the increase in N2O fluxes from added fertilizer, which together with the associated CO2 cost of fertilizer manufacture (see next section), can readily and negatively offset the net greenhouse gas benefit of additional soil C storage.

Greenhouse gas cost of fertilizer manufacture

The production and transport of fertilizer generates a significant proportion of the GHG emissions associated with crop production (Robertson et al. 2000). Estimates of actual emissions from current industrial fertilizer production vary considerably. Snyder et al. (2009) note estimates that range from 2.2 to 4.5 kg of CO2-eq kg−1 of NH3-N. The lower value is for NH3 production using best available technology and the higher value is for the current mix of N fertilizer sources used in the US, including the average GHG cost of transport. Production of ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) entails greater GHG emissions than for anhydrous NH3 or urea.

Only small increases in the efficiency of NH3 production are expected in the short-term. In the long-term, however, if a C-free method can be found to generate hydrogen for the Haber–Bosch process, NH3 could be produced with a much smaller C footprint.

In Europe, a large fertilizer producer has provided figures for the C footprint of its N fertilizer (Yara 2010). They report that manufacture of NH4NO3 generates 3.6 kg of CO2-eq kg−1 of N (2.2 for the NH4 + component plus an additional 1.4 for the NO3 −, using best available technology). The transport of the fertilizer adds a further 0.1 kg of CO2-eq kg−1 of N. In the US, if fertilizer plants were operated with the same best available technology for NH3 manufacture, a lower C footprint would be expected since NH4NO3 comprises only a small fraction of total N fertilizer use. North American producers of N fertilizers have demonstrated improvements in efficiency and have also committed to reducing the C footprint of N fertilizer manufacture to the extent possible.

Opportunities for climate mitigation/adaptation with N use

Much of the GHG forcing in agriculture by N can be reduced, avoided, or offset by N management practices that minimize GHG emissions and Nr escape, sequester C, and decrease the likelihood of converting land elsewhere to agricultural production. Many of the effects of these practices interact, so it is important to consider them in concert, from a systems perspective. While many effects are additive, they are combinable to different degrees in different crop and animal systems.

Agricultural intensification

Agricultural intensification can reduce GHG emissions by reducing the need to newly convert non-farmed areas to agricultural production. Burney et al. (2010) estimate that gains in crop yields since 1961 have, globally on a net basis, spared emissions of 320–590 Gt CO2-eq. They note that while emissions per unit area of intensified crop (i.e., a cropping system’s GHG intensity) are higher than those of lower-input crops, the emissions from land conversion associated with extensification are considerably larger. Converting land to crop production entails very large GHG emissions, for instance vegetation removal and the oxidation of SOM upon cultivation releases CO2 and may also affect the N cycle by increasing N2O production for several years following clearing, even in the absence of N fertilizer.

Burney et al. (2010) further noted that crop yields per unit area increased by more than two-fold from 1961 to 2005, which has limited the expansion in cropland area to 27 %. Without these yield increases, they estimated that approximately 300 % more land would have been required to attain the crop production levels of 2005. This foregone GHG release is an important benefit of intensification, especially as intensification could provide opportunities for management interventions not as easily provided in more dispersed systems. Burney et al. (2010) concluded that investment in research toward agricultural intensification (primarily higher crop yields) was a cost-effective approach to GHG mitigation, with overall costs of approximately US $4 per Gg of avoided CO2-eq.

Nitrogen management interventions for GHG mitigation in cropping systems

A variety of N management practices are available to reduce GHG forcing in cropping systems. These range from the way in which N fertilizer is applied, such as its rate, timing, placement, and formulation, and to changes in human diets. Many appropriate technologies are available now, and require only appropriate incentives to adopt. Other technologies are promising but unproven or not as generalizable.

Fertilizer rate, timing, placement, formulation, and additives

Applying the right source of N at the right rate, time, and place is the core concept of 4R Nutrient Stewardship, supported by a wide range of industry and government organizations (IFA 2009; Bruulsema et al. 2009). The 4R strategy is designed to increase crop NUE. In general, it is assumed that any practice that increases crop NUE is expected to reduce N2O, NO x , and NH3 emissions, because fertilizer N taken up by the crop is not available to the soil processes that lead to N emissions, at least in the short term. Thus, strategies to reduce losses of N are generally associated with improved fertilizer use efficiency.

Practices that improve NUE do not always reduce N emissions, however. Different fertilizer formulations, for example, can result in different N2O emissions regardless of putative NUE effects. Likewise, banded fertilizer placement can increase NUE but in some cases also increase N2O emissions, whereas tillage management can increase NUE without affecting N2O. Thus NUE is generally important but is not sufficient by itself to reduce N emissions. Fertilizer rate, timing, placement, and formulation can affect NUE and N gas emissions independently.

Fertilizer rate

More than any other factor, the amount of N fertilizer applied to soil affects the amount of N2O and NO x emitted—in many cases timing, placement, and formulation provide their benefit by effectively reducing fertilizer N in soil. In this sense, fertilizer rate is a good integrator of multiple practices (Millar et al. 2010).

Fertilizer timing

Synchronizing soil N availability with crop N demand is a major challenge for efficient fertilizer management. Typically fertilizer is applied well ahead of peak demand, sometimes as much as 6–8 months ahead of crop demand in the case of fall-fertilized corn in the Midwest. Although side-dressing fertilizer shortens this lag to weeks, there is still a period when Nr is more available to microbes than to roots. Moreover, N emissions are almost always greatest immediately following fertilization when soil N levels are high and temperature and moisture are sufficient for microbial activity.

Fertilizer placement

How fertilizer is applied to soil can affect its availability for crop uptake and also its susceptibility to soil transformations that produce N2O and NO x . Placement includes three broad strategies: (1) broadcast application vs. within-row banding; (2) the soil depth to which liquid fertilizer is injected; and (3) uniform application vs. application at different rates within the same field based on the variability of soil fertility across the field. The effects of banding and injection on N gas emissions are equivocal. Although banding can increase NUE, it can also create zones of highly concentrated soil N that can increase rather than decrease the production of N2O (Engel et al. 2010). Deep injection of liquid N almost always reduces volatilization of NH3 compared with the surface application of manure, urea, and other urea or NH3-containing fertilizers. However, effects on N2O production are inconsistent. Variable rate application uses different N rates for different areas of a field based on expected variations in crop N demand. This is a new technique and will be discussed more fully later.

Fertilizer formulation and additives

Anhydrous NH3 is the most commonly used synthetic fertilizer in the US (35 % of total use), followed by liquid formulations including urea NH4NO3 (29 %) and urea (24 %). Early studies found inconsistent effects of fertilizer formulation on N gas emissions; consequently IPCC GHG inventory guidelines (De Klein et al. 2006) make no distinctions among different formulations or between inorganic and organic forms, although recent cross-site research suggests higher N2O emissions with anhydrous ammonia than with broadcast urea (e.g., Venterea et al. 2010). Chemical additives such as urease and nitrification inhibitors delay the transformation of urea and NH4 +, respectively, to improve the synchrony between soil N availability and crop N demand. Delayed-release chemical formulations such as polymer coated urea slowly release N with increasing soil temperature and water to achieve the same effect. To date, effects of additives and chemical formulations on N2O emissions have been inconsistent, although recent meta-analyses (e.g., Akiyama et al. 2010) suggest that broader experimentation will provide greater clarity.

Integration

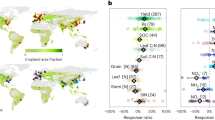

The 4R Nutrient Stewardship concept is designed to provide farmers a management paradigm that increases the sustainability of the plant system to which it is applied (Fig. 5). For any given system, performance includes the productivity and profitability of the system (the economic dimension of sustainability), its impacts on soil, water, air and biodiversity (the environmental dimension), and its impacts on quality of life and employment opportunities (the social dimension). Farmers ultimately choose the combination of practices that are judged to have the highest probability of meeting economic and environmental goals based on site-specific soil, weather, crop production, and local regulatory conditions. The 4R Nutrient Stewardship concept is a central component of the Alberta N2O Emission Reduction Protocol for C offset trading (Alberta Environment 2010) and is entrained in many US state Best Management Practice statutes.

The 4R nutrient stewardship concept guides farmers to apply N fertilizer in ways that maximize crop N use and minimize N loss to the environment. For any given crop, four decisions largely control fertilizer use efficiency: the source or formulation of the fertilizer (e.g., urea vs. manure); the rate or annual amount of fertilizer applied; the placement of fertilizer in the field (e.g., broadcast vs. subsurface vs. precision applied); and time of fertilizer application (e.g. fall pre-plant vs. at planting vs. during active crop growth). Decisions are informed by environmental, social, and economic concerns (IPNI 2012)

Precision fertilizer application technologies

Although not new concepts to US agriculture, precision technologies and site-specific N management continue to gain attention as potential methods to improve N fertilizer use and efficiency. Typically, these methods attempt to integrate fertilizer decisions with field-scale spatial and temporal variations in system characteristics such as soil chemical and physical properties and crop growth patterns. Farmers can now micro-manage their farms using tools such as global positioning systems (GPS) and geographic information systems (GIS) software. When combined with geo-referenced sampling and variable rate application technology, farms are able to more closely match fertilizer applications with crop requirements and thereby improve NUE and reduce environmental losses of Nr.

An example of the potential impact of precision farming technologies on N management is the growing interest in crop canopy sensor use. Recently, numerous investigations have explored the use of remotely-sensed crop spectral data as a means to understand plant growth characteristics and improve N management for several crops (e.g., Raun et al. 2002). The remotely-sensed normalized difference vegetative index (NDVI) is a measure of total above-ground green biomass and is an indicator of crop growth and health. Use of canopy reflectance and NDVI as an in-season assessment of crop yields can be a valuable tool to fine-tune N management, optimizing crop N fertilizer recovery. Historically, published reports of NDVI data have been remotely-sensed using passive sensing methods such as aerial and satellite imagery. More recently, numerous studies have specifically reported the use of active-light, crop canopy reflectance sensors as a promising tool to improve N use efficiency by estimating N requirements and yield potentials for crops including corn, wheat, and sugar beets (Raun et al. 2002, 2005; Girma et al. 2006; Freeman et al. 2007; Dellinger et al. 2008; Barker and Sawyer 2010; Kitchen et al. 2010; Gehl and Boring 2011).

Beyond in-season N management, NDVI has also been used as a predictor of N management zones for subsequent crops. Franzen (2004) describes the widespread use of satellite NDVI images for sugar beet canopy N credits to develop N management zones for adjusting N rates for the next crop in the rotation. Continued improvements and advances in available site-specific technologies will increase future opportunities for Nr mitigation at the farm field-scale by more closely matching inputs with crop needs.

Tillage practices

The effect of changes in tillage management on soil N emissions is variable and not fully understood. Short-term studies have documented increases, decreases, and no changes in soil N2O emissions with the adoption of no-till, with responses being principally related to soil texture and structure, climate, fertilizer placement, and time since adoption. In a recent meta-analysis, Six et al. (2004) found that N2O emissions are in general higher in the first 10 years after adoption of no-tillage, but over time emissions tended to be lower in humid climates and the same in dry climates. However there are many sites where this generalization does not fit and clarity awaits further research.

Ozone resistant crop cultivars and methane mitigation

Increasing evidence points to elevated O3 concentrations as being an important and usually overlooked stress in the deceleration of global crop yield increases (Avnery et al. 2011a; Fishman et al. 2010; Van Dingenen et al. 2009; Zhu et al. 2011; Wang and Mauzerall 2004). Recent model simulations quantified the present and potential future (year 2030) impact of surface O3 on the global yields of soybean, maize, and wheat given both upper- and lower-boundary projections of reactive O3 precursor emissions (Avnery et al. 2011a, b). Avnery et al. (2011b) projected substantial future yield losses globally for these crops even under a scenario of stringent O3 control via traditional pollution mitigation measures (i.e., reductions in NO x , VOCs, and NMVOCs): 10–15 % for soybean, 3–9 % for maize, and 4–17 % for wheat.

Given the potential for significant future O3-induced yield losses, two additional strategies to reduce O3 impacts should be considered: (1) O3 mitigation through CH4 mitigation, and (2) adoption of ozone-resistant cultivars. Methane is both a GHG and an O3 precursor and reductions in CH4 thus provide benefits to human health and vegetation including crops. Avnery et al. (2011a) found that gradual reductions in CH4 emissions between 2005 and 2030 could increase global production of soybean, maize and wheat by 23–102 Tg in 2030, which is the equivalent of a 2–8 % increase over year 2000 production, worth US $3.5–15 billion worldwide (USD2000). A wide variation in O3 sensitivity exists both between crops and among crop cultivars. As noted earlier, analyses using minimum and median concentration–response relationships to O3 exposure obtained from the US NCLAN (Heck 1989) showed that the use of existing cultivars with minimum sensitivity to O3 could increase global yields of corn, wheat and soybean 12 % over year 2000 production by 2030 (Avnery et al. 2011a). Combining CH4 mitigation with O3-resistant cultivars would yield the greatest gains to agriculture, although benefits are less than fully cumulative given the nature of the effect of O3 on crops. In any case, there appears to be significant potential to improve global agricultural production without further environmental degradation by reducing O3-induced crop yield losses via reductions in O3 precursors (i.e., NO x , CO, VOCs, and CH4) and by the development and utilization of O3 resistant crop cultivars.

Perennialization of fields and landscapes

The winter and early spring fallow period common to row crop agriculture creates a significant opportunity for Nr loss (Blevins et al. 1996; Wagner-Riddle and Thurtell 1998; Strock et al. 2004; Dusenbury et al. 2008). Nitrogen that remains in the soil after the summer annual crop is removed is susceptible to loss by leaching (as NO3 −) or denitrification (N2O, NO x , N2), particularly if no crop or vegetation is present for N uptake during the off-season and precipitation is sufficient (Dorsch et al. 2004). Winter cover crops can be used to “perennialize” an annual cropping system by providing nearly year-round plant production, as can the use of perennial rather than annual crops for biofuel feedstocks (Robertson et al. 2011).

The presence of living plants during the winter season can reduce Nr losses through mechanisms of plant N uptake and reduced subsurface percolation. Cover crops have been documented to reduce both N2O flux and NO3 − leaching compared with bare fallow systems (McSwiney et al. 2010). This effect is especially pronounced where manures have been applied after the primary crop growing season (Parkin et al. 2006). However, recent research has indicated that N fertilizer rate may be more influential to N2O emissions when compared with the presence of a cover crop, regardless of cropping system and manure application (Dusenbury et al. 2008; Jarecki et al. 2009)

The establishment of perennial vegetation on cropland can also reduce Nr losses. Whether established for conservation purposes such as the US Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) or established for cellulosic biofuel production, perennial grasses and short-rotation trees conserve both N and soil C. The rooting system of some C4 perennial grasses can contribute up to 2.7 Mg C ha−1 year−1 to the top 5 cm of soil (Lemus and Lal 2005; Schmer et al. 2011). For example, estimated total C mitigation for giant miscanthus was estimated at 5.2–7.2 Mg C ha−1 year−1 over the course of a 15 year study in Ireland (Clifton-Brown et al. 2007).

Proposed perennial biomass crops generally require relatively low fertilizer N additions for maximum crop growth and consequently can exhibit low N2O emissions (Jørgensen et al. 1997) and other N cycle benefits such as lower NO3 − leaching (Robertson et al. 2011). Davis et al. (2011) estimate, using the DAYCENT model, that conversion of US cropland currently used for corn grain ethanol production to perennial cellulosic feedstocks would increase both ethanol and feed production while reducing NO3 − leaching 15–122 % and GHG emissions 29–473 %. Empirical research is needed to further improve our understanding of the effects of landscape-level land conversion to perennial biofuel feedstocks on Nr system dynamics.

Perennialization can also occur as the result of strategic conservation plantings in the landscape. Grass or other vegetative buffer strips in specific topographic locations can intercept NO3 − flowing to groundwater and streams, as can natural or restored wetlands, avoiding its conversion to N2O and NO x further downstream (Robertson et al. 2007). Although some N2O is likely to be produced at the point of interception, the presumption is that this will be less than would occur were the Nr allowed to proceed unabated.

Models and other decision support tools

The complexities of the processes that govern soil Nr transformations complicate N fertilizer management decisions for the farmer. These processes are both dynamic and site-specific, requiring growers to make decisions based on past experience while anticipating likelihoods for the current growing season. In essence, growers must plan and manage N fertility programs that are most likely to give the greatest economic yield. As such, a system of support tools becomes critical to assist growers with N fertilizer decisions.

Crop response to applied N varies spatially, both among and within fields, and temporally, from one year to the next. The shape of the crop response curve determines the appropriate fertilization rate. For many crops, the most economic N rate prevents loss of large surpluses and comes close to minimizing emissions of N2O per unit of crop produced (van Groenigen et al. 2010).

The crop response curve to N additions is unknown at the time of fertilizer application because of uncertain future rates of N mineralization from SOM. Therefore, the decision on the appropriate N rate must be made using tools or systems that forecast the most likely crop N response given soil, crop and weather conditions. Recommendation systems in the US are typically state-specific and vary in approach. Historically, recommendations were primarily based on predicted yield models, but more recently many states have moved toward economic response models that may or may not include predicted yield. An example is the maximum return to N (MRTN) recommendation tool recently adopted by seven Midwest states. The MRTN approach uses recent response trial data from individual state or local regions to determine the N fertilizer rate where economic net return to N application is greatest (Sawyer et al. 2006). The MRTN is a regional model based on historic response curves for specific geographies. As a decision support tool, the factors used in generating the recommendation include fertilizer and crop prices.

An approach that goes further toward including additional factors relevant to N rate prediction are process-based models such as Maize-N (Setiyono et al. 2011) and System Approach to Land Use Sustainability (SALUS) (Basso et al. 2011). While this approach is more deterministic and less empirical than MRTN, it is still based on historical climate data and could be adapted to anticipate dynamic weather conditions that influence the prediction of potentially attainable yields and yields without N fertilizer.

Weather controls a great deal of the variation in a crop’s response to N. The application of models integrating soil water flow, soil N dynamics, and plant uptake can potentially improve the prediction of crop N needs in response to weather conditions. An example of a model that includes dynamic weather factors is Adapt-N (Moebius-Clune et al. 2011).

Nutrient management becomes more complex when animal manure is used in the cropping system. Since the relative concentrations of manure nutrients (e.g., the N:P ratio) are fixed, it is more difficult to match available nutrients to crop needs. Nutrient management plans are generally designed to assure that manure nutrients are applied at the appropriate time and rates for crop use, thus reducing losses to the environment. Software tools such as the Manure Management Planner (Joern 2010) assist producers in the development of nutrient management plans that make best use of available manure nutrients along with inorganic fertilizers.

Animal system N management practices that mitigate GHG forcing